The Problem with "Optimizing" Our Lives

The danger in seeing the totality of our lives as something to be "optimized" or "solved" as opposed to experienced, and a suggestion for pushing against such a mindset.

Several years ago, I moved away for graduate school and arrived in an unfamiliar city where I knew few people. Unsurprisingly, I started to feel lonely. I had my schoolwork and consulting work, some friends and family in the area, but overall, I did not feel that I was flourishing. The solution to this was to patiently keep doing what I was doing already: attending events to meet new people, focusing on enjoyable hobbies and activities, and taking advantage of the extra time to deepen my intellectual and prayer life. The key was patience.

But I wanted a shortcut.

Around this time, I started listening to podcasts and reading articles on building daily routines and adopting certain habits to feel better and live healthier. I started to believe that this could be a more immediate and direct way to feeling better overall. I thought that maybe my predicament could be solved through some tinkering of my body’s mechanics. So, I began working out for 150 minutes every week, trying to get at least seven hours of sleep, exposing myself to sunlight first thing in the morning to trigger dopamine release for a healthy circadian rhythm, increasing my Vitamin D and Omega-3 consumption, and so on. And I did start to feel better, believing I had stumbled upon a solution to my restlessness. Yes, I thought, it had been a simple failure of action on my part. I had within my control the tools to ensure I felt good most of the time.

I didn’t believe this would solve all my problems, of course, and it didn’t. But I did view it as a means of controlling my situation. It offered the illusion of a remedy, which I found comforting at the time. If I felt down or disappointed about something, like receiving frustrating news at work or having an argument with a friend, I could deal with these negative feelings by tweaking my body’s chemistry: taking supplements to boost mitochondria activity or enduring cold showers to release feel-good endorphins. I could manage my feelings through my knowledge, my will.

I don’t think my experience is an uncommon one. There are a lot of resources these days offering insights and tips for living “optimally,” such as The Huberman Podcast, The Happiness Lab, WorkLife, 10 Percent Happier, and others. Many of these podcasts offer useful information, enabling us to apply insights from scientific research to better take care of ourselves. I’m grateful for them, and I think they can be helpful. They offer us an opportunity to be better stewards of our bodies, and since we are body-soul composites, this can lead to being better stewards of our souls. What I’m interested in pointing out, though, is how they can slowly shape our mindset to such that, even if only subconsciously, we begin to approach our lives as a series of experiences to be solved, manipulated, or optimized.

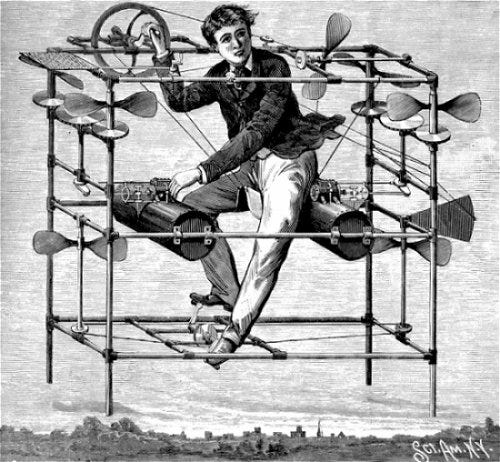

I’m reminded of Gilbert Ryle’s phrase “the ghost in the machine,” which touches on the Cartesian theory that mind and body are composed of unique substances. Ryle used the term to ultimately criticize the bifurcated view of the mind and body, though it remains an apt metaphor for depicting the body as a type of vessel or “machine,” something separate from the soul that can, nevertheless, be shaped for the soul’s purposes. I think such a view relates to this temptation to view negative emotions, feelings, and, well, all undesirable subjective experiences as the result of mechanistic functions of the body that need to merely be tweaked, like a faulty machine requiring the application of a new part for repair. Again, most of us don’t consciously view ourselves in such a way, but I think the subtle danger is more or less subconsciously living our lives as such.

Let me introduce another idea that, I think, will be helpful to consider. The technology theorist Jacques Ellul wrote about the notion of technique in his classic The Technological Society. In the book, he describes technique as that which “clarifies, arranges, and rationalizes; it does in the domain of the abstract what the machine did in the domain of labor. It is efficient and brings efficiency to everything.” Technique for Ellul might be understood as a collective mindset, a type of paradigm that has for its ends efficiency and order.

Technique is admittedly a complex term, and while we cannot reduce it to a tendency to follow certain procedures to reach a goal, the element I want to focus on is that, according to Ellul, “efficiency” is the highest good. In such a society, our freedom is curtailed because our decisions are guided by that which is most efficient. I think there are strands of this that explain my approach to life a few years ago, and something that I see a fair amount of in our culture today. All of these self-help and “optimize-your-life” resources can train us to ever be on the lookout for ways to be more efficient: diets and exercise routines to maximize strength and viability, scheduling hacks to make the most of our workday, sleep- and heart-tracking technologies to probe and augment physical health, and so on. Thus, more and more of our decisions are fueled by what is most “efficient” or “optimal.”

However, if we are constantly striving to achieve an optimal state through diet, exercise, meditation, supplements, more social interaction, etc., we can forget that our experience of life, even and especially its unpleasant aspects, is a divine mystery to be embraced and not a project to be solved or maximized. Obviously, we should do what we can to be healthy and productive, but without losing sight of what matters most in our lives—namely, loving God and others.

This can be especially important to keep in mind when it comes to our spiritual lives since here, too, we can allow a type of “optimizing mindset” to creep in. If we are subconsciously treating ourselves as “machines,” always trying to manipulate our bodies and subjective states, we can impede our spiritual efforts. Instead of asking God in prayer to make us humble and forgiving, for instance, we might unconsciously be putting our faith in the “right” meditation practice or mood-boosting habit. In other words, the vices of irritability or resentment are reduced to physiological abnormalities in need of, say, a supplement instead of a deficiency in our souls in need of God’s grace. We can even do the same thing with prayer. Prayer can become a means of simply feeling better, or providing mental clarity, or restoring our energy—more therapy than communion with the God who loves us and wants a relationship with us.

I think the prayerful practice of Memento Mori (“remember you must die”) is one powerful way of keeping our physical decay and eventual death front and center of our minds and hearts. It’s a reminder that no matter what we do to “live optimally,” we will eventually die. Yes, but it’s also a reminder that our ultimate hope is found in God alone, not in our own efforts, routines, schedules, diets, will, or knowledge. And it’s a reminder that some of the suffering we endure cannot and, perhaps, should not be “solved” but, rather, experienced as a gift for mysteriously growing in faith, hope, and love. Finally, I think it’s a reminder that we were created not to be carnal “machines” primed for continuous optimization but human beings made to give and receive God’s love.